The Critical Skill for a Complex World: Why You Need to Think Better

From the workplace, where effective problem-solving and strategic planning are essential, to your personal life, where filtering misinformation is vital, strengthening this cognitive muscle is an investment in your future. Suppose you’re ready to move beyond passive information consumption and start engaging with the world in a deeper, more analytical way. In that case, these 9 best critical thinking exercises will provide the structured practice you need to transform your mental process and dramatically improve decision-making skills.

The 9 Best Critical Thinking Exercises

These exercises are structured to develop different facets of critical thinking, from logic and analysis to perspective-taking and evaluation.

1. The Socratic Questioning Method

This exercise is named after the classical Greek philosopher Socrates and is arguably the most powerful tool for intellectual exploration. It’s a method of disciplined, open-ended questioning used to explore complex ideas, surface assumptions, and identify underlying truths.

How to Practice:

- Select a Topic: Choose a complex belief, a recent decision you made, or an ethical dilemma.

- Ask Questions of Clarification: What exactly do you mean by X? Can you give me an example?

- Probe Assumptions: Why do you believe that to be true? What if you assumed the opposite?

- Explore Different Perspectives: How would a person with a radically different background view this? What counterarguments exist?

- Identify Consequences: What would be the long-term impact of this belief or decision? How does this affect Y?

Skill Developed: The Socratic Method builds the ability to challenge assumptions, ensuring your conclusions are based on solid evidence, not just initial feelings or unexamined beliefs. It’s the foundational critical thinking exercise for deep analysis.

2. Argument Mapping (Visual Logic)

Argument mapping is a visual exercise that forces you to break down a complex argument into its core components—claims, evidence, and objections—and show the logical relationships between them.

How to Practice:

- Choose an Argument: Pick a thought-provoking article, op-ed, or political debate.

- Identify the Conclusion (The Main Claim): This is the final point the author is trying to prove.

- Map the Premises (The Supporting Reasons): List all the pieces of evidence, data, or reasons used to support the conclusion.

- Draw the Structure: Use a diagram (or software) to connect the premises to the conclusion with arrows, clearly showing which pieces of evidence work together to support the final claim.

- Add Counter-Arguments: Insert any objections or counter-evidence that the author did not address, evaluating how they weaken the main conclusion.

Skill Developed: This exercise enhances structural analysis and the ability to evaluate the validity and soundness of a claim. You visually identify weak links in the chain of reasoning, making it one of the most effective critical thinking activities for academic or professional analysis.

3. Fact vs. Opinion vs. Inference

A primary function of critical thinking is distinguishing between objective reality and subjective interpretation. This exercise trains your mind to categorize information accurately, which is essential for avoiding misinformation.

How to Practice:

- Gather Statements: Take a paragraph from a news article, a social media post, or a book.

- Identify Facts: Statements that can be proven true or false with verifiable evidence (“The meeting starts at 3:00 PM”).

- Identify Opinions: Statements that reflect a belief, judgment, or feeling (“The presentation was boring”).

- Identify Inferences: Statements that are logical conclusions drawn from facts, but are not facts themselves (“Since the meeting was moved up an hour, the organizers must be running behind schedule”).

- Reflect: Ask yourself: Did I mistake any opinion or inference for a fact? What evidence would turn the inference into a fact?

Skill Developed: This is an invaluable critical thinking drill for improving information literacy and separating subjective bias from objective evidence in all forms of communication.

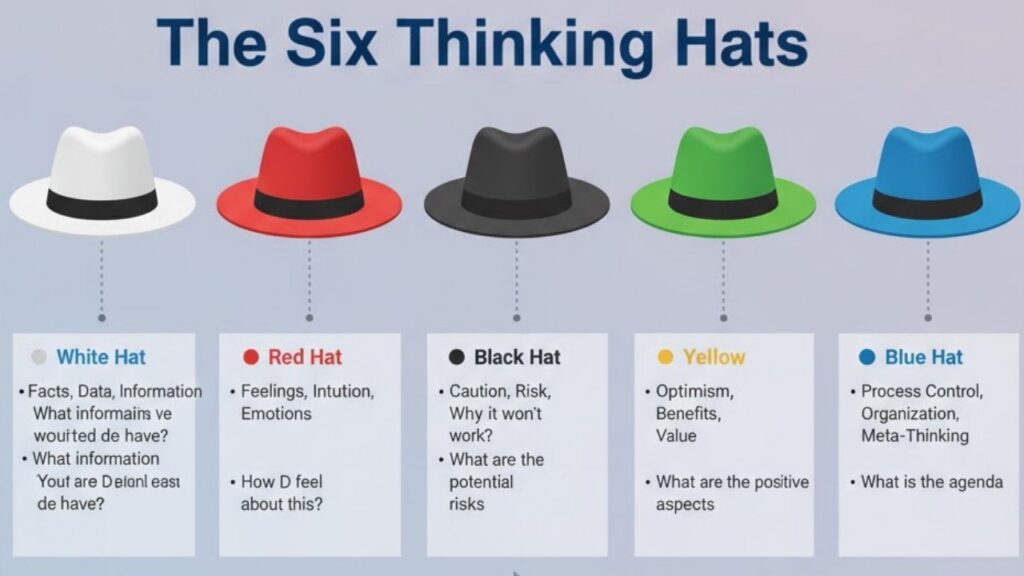

4. The Six Thinking Hats (Dr. Edward de Bono)

The Six Thinking Hats is a parallel thinking process designed to separate different types of thinking and move a discussion or decision-making process forward constructively. Instead of everyone debating from different perspectives simultaneously, participants “put on” one hat at a time, directing all thinking in a single, focused direction. This structure helps to avoid confusion, allows for the inclusion of emotions and creativity in an organized manner, and ensures all angles are considered.

The Six Hats and Their Focus:

| Hat Color | Thinking Focus | Questions to Ask |

| ⚪ White Hat | Facts, Data, Information | What information do we have? What information is missing? What are the facts? |

| 🔴 Red Hat | Feelings, Intuition, Emotions | How do I feel about this idea? What is my gut reaction? What are the emotional responses of others? (No justification needed) |

| ⚫ Black Hat | Caution, Risk, Why it won’t work | What are the potential risks? What are the drawbacks? Why might this fail? Is this feasible? |

| 🟡 Yellow Hat | Optimism, Benefits, Value | What are the positive aspects? What is the value or potential benefit? Why is this a good idea? |

| 🟢 Green Hat | Creativity, New Ideas, Alternatives | What are new ideas or alternatives? Can we look at this in a completely different way? How can we overcome the Black Hat difficulties? |

| 🔵 Blue Hat | Process Control, Organization, Meta-Thinking | What is the agenda? What hat should we use next? What have we achieved so far? (This hat manages the session). |

Application

The Blue Hat typically starts and ends the session, setting the focus and summarizing the outcome. A common sequence might be: Blue (set agenda) $\rightarrow$ White (facts) $\rightarrow$ Green (generate options) $\rightarrow$ Yellow (look for benefits) $\rightarrow$ Black (evaluate risks) $\rightarrow$ Red (gut check) $\rightarrow$ Blue (summarize and decide on next steps). This technique ensures that pessimism (Black Hat) and optimism (Yellow Hat) are used constructively and separated from the creative process (Green Hat) and objective facts (White Hat).

5. Root Cause Analysis: The 5 Whys

The 5 Whys technique is a simple but powerful method of Root Cause Analysis (RCA) for exploring the cause-and-effect relationships underlying a particular problem. The goal is to determine the underlying cause of a defect or problem by repeatedly asking the question “Why?” until the root issue is uncovered.

The Process

- Start with the Problem: Clearly state the problem or failure.

- Ask “Why?”: Ask why the problem occurred, and write down the answer.

- Repeat: For each subsequent answer, ask “Why?” again. This directs the current “why” to the answer of the previous “why.”

- Stop at the Root Cause: Continue asking “Why?” until you reach a root cause—a cause whose removal or modification will prevent the final effect’s recurrence. This often takes about five iterations, but could be fewer or more.

Example

Initial Problem: The machine stopped unexpectedly.

- Why did the machine stop? $\rightarrow$ Because the belt broke.

- Why did the belt break? $\rightarrow$ Because it hadn’t been replaced on the scheduled maintenance cycle.

- Why hadn’t it been replaced on the scheduled cycle? $\rightarrow$ Because the maintenance schedule was based on time, not usage.

- Why was the schedule based on time, not usage? $\rightarrow$ Because the old maintenance process didn’t account for variable production load.

- Why didn’t the old process account for variable production load? $\rightarrow$ Because the initial process design was outdated and had never been reviewed for changes in operational practice.

- Root Cause: The maintenance process is flawed and hasn’t been updated to reflect current operational reality. The solution moves from simply replacing the belt (a symptom fix) to reviewing and updating the maintenance schedule (a root cause fix).

6. Lateral Thinking Puzzles and Mindsets

Coined by Edward de Bono, Lateral Thinking is a way of solving problems by approaching them indirectly and creatively, using reasoning that is not immediately obvious. It contrasts with Vertical Thinking, which is the conventional, logical, step-by-step approach.

The Value of Lateral Thinking

- Breaks Assumptions: Lateral thinking puzzles and exercises challenge you to identify and question the hidden assumptions that limit your thought process.

- Generates Alternatives: It encourages the search for multiple possibilities, rather than simply pursuing the most logical single path.

- Sparks Creativity: It is a key tool for innovation, helping to generate “out-of-the-box” solutions.

Application

Lateral thinking is often practiced through puzzles where the answer seems counter-intuitive until a key assumption is identified and suspended. Engaging with these puzzles helps train the mind to look beyond the obvious constraints.

7. Pre-Mortem Analysis

The Pre-Mortem is a project management strategy that involves imagining, before a project begins, that it has completely failed. The team then works backward to identify all the potential reasons for that failure. This technique is a form of prospective hindsight, aimed at proactively identifying and mitigating risks.

Steps to Conduct a Pre-Mortem

- Define the Project and Success: Clearly define the project, its goals, and what success looks like.

- Set the Scene (Imagine Failure): Gather the team and announce, “The project has failed spectacularly. It’s six months from now, and it was a total disaster.”

- Brainstorm Reasons: Each team member, individually and silently, writes down every plausible reason they believe the project failed. They should be encouraged to be creative and detailed.

- Consolidate and Share: The reasons for failure are collected and read aloud (to ensure no bias against the person suggesting the risk) and then grouped into common themes (e.g., “Communication Failure,” “Technical Debt,” “Resource Scarcity”).

- Develop Mitigation Strategies: For the most critical or likely failure themes, the team brainstorms and assigns concrete, actionable steps to prevent that failure from occurring.

- Review and Revise: The project plan is updated to incorporate the newly identified risks and their mitigation strategies.

The pre-mortem surfaces hidden risks and blind spots that might not come up in a typical risk assessment, as the mindset shift encourages honest, pessimistic, and creative foresight.

8. Recognizing and Mitigating Cognitive Biases

Cognitive Biases are systematic patterns of deviation from norm or rationality in judgment. They are mental shortcuts (heuristics) that our brains use to make sense of the world quickly, but which can lead to flawed reasoning and poor decisions. Critical thinking requires constant vigilance against these biases.

Key Cognitive Biases to Address

| Bias Name | Description | Impact on Thinking |

| Confirmation Bias | The tendency to search for, interpret, favor, and recall information in a way that confirms one’s pre-existing beliefs or hypotheses. | Leads to one-sided research, ignoring contradictory evidence, and overconfidence in flawed conclusions. |

| Availability Heuristic | Judging the likelihood of an event by how easily examples of it come to mind. | Overestimating the probability of memorable (often sensationalized) events, regardless of actual statistical frequency. |

| Anchoring Bias | Over-relying on the first piece of information offered (the “anchor”) when making decisions. | Skewing subsequent estimates, negotiations, or evaluations based on an often arbitrary starting point. |

| Sunk Cost Fallacy | Continuing a course of action because resources (time, money, effort) have already been invested, even if continuing is irrational. | Prevents abandoning failing projects, leading to further losses. |

Mitigation Strategy: Bias Journaling

To mitigate biases, maintain a Bias Journal where you:

- Identify a Recent Decision: Note a significant decision or conclusion you reached.

- List the Evidence: Write down the information you used to make that decision.

- Reflect on Biases: Review the evidence and your process, asking questions like: Did I only look for evidence that supports my initial idea (Confirmation Bias)? Did I dismiss a valid alternative because it seemed too complex (Availability Heuristic)?

- Articulate the “Anti-Thesis”: Force yourself to articulate the best possible argument against your conclusion, using contradictory data.

9. The “What’s at Stake?” Exercise

This exercise is not a formalized technique but a powerful principle applied in critical thinking to elevate motivation and focus. It forces a deep, values-based analysis of the consequences of success and, more importantly, failure.

The Exercise

Before beginning a major endeavor or making a critical decision, a team or individual explicitly defines and discusses:

- What success enables (The Payoff): What are the tangible and intangible rewards of getting this right? (e.g., Launch of new product, securing funding, saving time/money, establishing trust).

- What failure costs (The Stakes): What are the highest-consequence results of getting this wrong? Be detailed and honest. (e.g., Financial ruin, loss of reputation, missing a key market window, damaging public trust, ethical harm).

Final Thoughts: Making Critical Thinking a Habit

Critical thinking isn’t a subject you study; it’s a mental habit you cultivate. The journey from passively accepting information to actively questioning it requires consistent effort. By regularly incorporating these 9 best critical thinking exercises—from the rigorous structure of argument mapping to the intellectual humility of Socratic questioning—you are equipping yourself with the tools to navigate a world that is only becoming more complex.

Start small: dedicate just ten minutes a day to one of these drills. Over time, you’ll find that the deliberate process of analysis, evaluation, and synthesis will move from a structured exercise to an automatic, indispensable part of how you think, empowering you to make clearer decisions and lead a more thoughtful life.

See Also: What to Do if Martial Law is Declared: Your Survival Guide